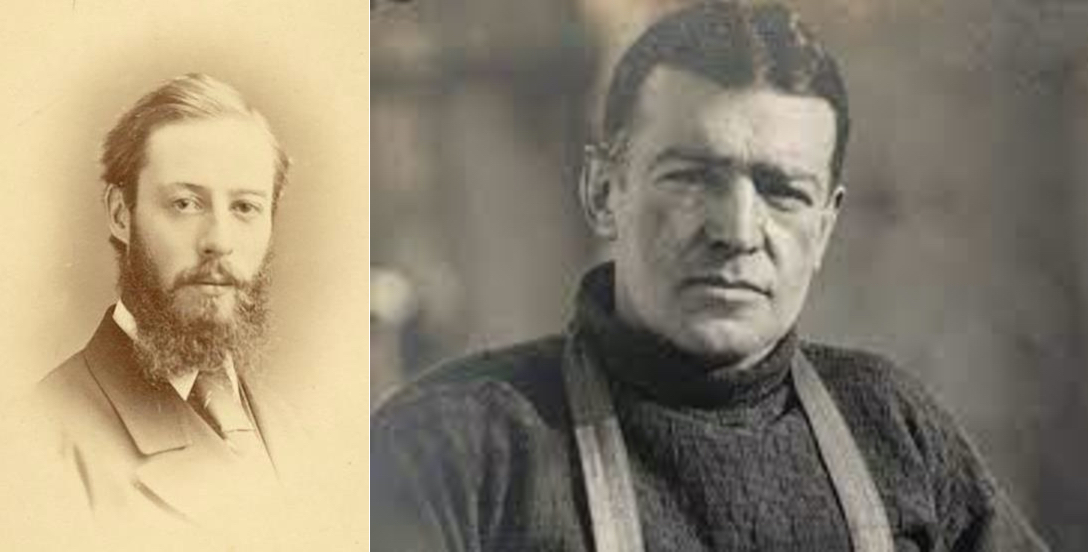

L to R – Alexander Pearce and Sir Ernest Shackleton

Recently I organised a lunch for old football team mates from the 80’s and 90s.

Not having seen many of them over the past thirty years, I wasn’t sure what to expect in terms of their physical health.

As a near sixty year old, I would consider myself to be in a serviceable condition but now unable to play any competitive sport or even run due to numerous surgeries and chronic arthritis.

To my surprise I was greeted not with expected ridicule, but with empathy as my old team mates rattled off a litany of their own ailments from new hips, to reconstructions and replaced knees.

Our late Mum always said “there are always others worse off than yourself” if ever we drifted into self-pity over something. Of course my younger brother Glen always retorted, “there is no one worse off than us!” which always got a laugh, but Mum was right.

It’s a mantra that has helped me a lot over the years confronting different challenges and most recently during almost two years of lockdown in Melbourne.

One only had to think of the medical staff on the frontline of Covid and any thoughts of playing victim quickly subsided.

There are however some stories where overcoming adversity reaches such extremes that surely there must be a third party engaged in maintaining the status quo.

A most recent example of this could be Neale Daniher’s fight with MND. Neale has proven that with purpose, faith and positivity, the extraordinary can be achieved.

Two of the most incredible stories of survival and greatest examples of overcoming adversity occurred well over a century ago, one in Tasmania and the other a bit further south in The Antarctic.

I first discovered the story of Alexander Pearce via a song written by Mick Thomas and performed by his band Weddings Parties Anything. The song, A Tale They Won’t Believe and the album, The Big Don’t Argue, were released in 1989 and both became instant Australian classics.

I initially thought the story of the convict party in the song was fictional but to my disbelief this wasn’t the case.

Alexander Pearce was transported from Ireland to Hobart for stealing some shoes in 1819.

After escaping and being re-captured he was sent to Sarah Island in the wilderness of Tasmania’s North West. He then escaped in the middle of winter with seven others and headed to Hobart, almost 200km south east through insufferable terrain.

His story of survival over four freezing months, consisting of murder and cannibalism is ‘edge of your seat’ stuff. After finally making it to Hobart alone, Pearce confessed to the authorities seeking a pardon but was sent straight back to Sarah Island.

After a year he escaped again with a young fellow convict named Cox. When he was eventually found, he still had some stolen rations along with various body parts belonging to Cox, in his pockets.

Ultimately hanged in Hobart in 1824, the story of Alexander Pearce is a brutal one but equally fascinating at how his world disintegrated from shoe thief to desperate cannibal.

There are two excellent books on the story of Alexander Pearce, Bloodlust and Hell’s Gates.

There is also a superb depiction of the journey from Sarah Island to Hobart in the film Van Dieman’s Land. Here is the trailer:

Whereas Pearce’s experience and mental toughness was cemented through fear, Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton was naturally fearless.

Anyone in that early 1900’s period that went searching for the South Pole must surely have had a ‘couple of roos loose in the top paddock’.

Legends such as Amundsen, Scott and Shackleton were so poorly equipped for such extreme conditions it was sheer luck in most cases that enabled their existence.

In Shackleton’s biography written by fellow explorer Ranulph Fiennes, you get taken on a journey like no other.

What makes the book so authentic is that Fiennes himself is one of the world’s greatest polar explorers and has set new records circumnavigating both Poles.

His insights provide clarity in what appears to a layman like myself, to be nothing short of sheer insanity.

Shackleton made three trips to the Antarctic. The first was with Robert Scott on the ship Discovery, where they got to within 500 miles of the South Pole. Unfortunately Shackleton contracted scurvy and upon their return to base camp, was sent back to England.

Determined to prove Scott wrong he organised his own trip, this time on the ship Nimrod. At this point of the book, just the descriptions of life on a wooden ship with crew, dogs and even donkeys navigating their way through ice for months on end is chilling enough.

The journey was a success with Shackleton breaking Scott’s record and getting within 80km of the South Pole before making the heartbreaking decision to head back in order to save his colleague’s lives.

He returned to England a hero and delivered countless lectures after which he donated most of his earning to local hospitals and charities.

Soon, he was bored again and discovering that the South Pole by that time had been reached by both Norwegian Roald Amundsen and Scott, the latter losing his life in the process, it was time to go back.

Given the race for the South Pole was over, Shackleton focused on something different, a Trans Antarctic Expedition in 1914.

It meant two teams. The Aurora would sail from Hobart to the southern tip of the continent and Shackleton’s ship the Endurance would sail from England to the northern tip.

The idea was that the southern team would build supply depots for Shackleton’s team to access on their journey of almost 3000km, in order to survive the extreme conditions.

Sadly all plans went out the door when the Endurance was closing in on the continent.

Upon reaching the ice barrier near Antarctica, the Endurance got stuck. This is where Shackleton’s phenomenal leadership skills kicked in.

At this point, he directed his men, dogs and lifeboats to safety and off the ice to Elephant Island, some 500km from the Endurance, which was by now literally being swallowed up by the moving ice and deposited 10,000 feet to the floor of the ocean.

I was so engulfed in the story at that stage, I weakened and looked on youtube for any footage. Given it was 1914 I wasn’t confident, but the Australian photographer Frank Hurley was there.

This remarkable footage shows the slow death of the Endurance and gave away a little of what I was about to read.

So it’s here where things get hairy. Shackleton decides that he must leave twenty odd of his crew on Elephant Island and with five others, sail a lifeboat 700 miles on open water filled with icebergs, killer whales and treacherous waves including a tidal wave.

They somehow reached the southern part of South Georgia Island after two weeks at sea but utterly exhausted, they couldn’t risk sailing again to reach the whaling station in the north.

Instead Shackleton and two others trekked north through the centre of the island over previously uncharted and freezing mountainous terrain with screws and nails pushed into their boots for traction.

Another miraculous three day and 50km journey completed, Shackleton and his two compatriots had their first wash in seven months at the whaling station.

It was from there they sailed to pick up the other two they left behind, then on to Chile to find a ship to rescue the remaining members of the team on Elephant Island.

Upon returning to England and with WW1 raging, Shackleton sailed to the second original camp at the southern tip of Antarctica to extract the team that had been stranded there for over two years.

Alas, three men in the team had perished attempting to build the supply depots for Shackleton’s Trans Continent Expedition. Shackleton took full responsibility and was never quite the same upon his return to England.

After helping his Motherland where he could in the last stages of the war, Shackleton would do one more trip south but died on the way from heart failure and was fittingly buried on South Georgia Island.

Fienne’s brilliant book genuinely takes you on Shackleton’s incredible life journey. For me:

I felt the relentless cold, the constant dampness, the freezing gale force winds, the frostbite, the sad reality of killing dogs and donkeys for food, the severe risks of moving ice, deadly crevices, the scurvy, the diarrhoea, the lack of sleep, the starvation, the fatigue and constant ‘running on empty’ and the reality that any sweat formed on the body would turn into ice and tear away layers of skin.

It’s been a bit cold lately in Melbourne.

The next time I look outside and hesitate when I know it’s time for a walk, I now feel the spirit of Pearce and Shackleton propelling my soft and reluctant body off the couch and out the door with a reinvigorated perspective on what adversity actually means.