We all know someone, perhaps even ourselves who have lost someone young. If that is the case then I just want to advise that this blog relates to someone who passed away prematurely, so if that is likely to cause emotional distress please stop reading now. Thankyou.

The accident

Andrew was 22, an engineering graduate from Duntroon and was in his last week of pilot training at the Oakey Army Aviation Centre, Queensland when he crashed in the low flying area of the stark, treeless plains on the outskirts of the base. He was flying a Bell 206B helicopter at over 200 kph and only a couple of metres off the ground. This wasn’t unusual for the pilots to execute but sadly on this particular day in 1985 Andrew made a critical mistake and one of the skids (undercarriage) touched the earth. Andrew was killed instantly. The transmission and engine that were directly above him, penetrated the cockpit and he was found in his seat buried 3 x feet into the Darling Down’s clay.

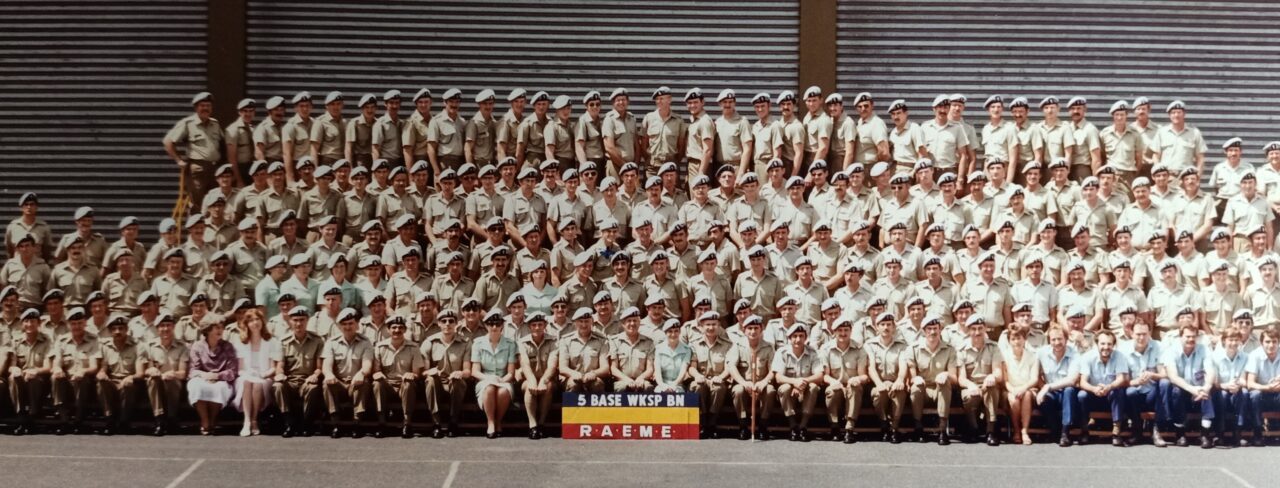

The whole of 5 Base Workshop Battalion where I was working, were utterly shattered. None of us were privy to the “why” and air crash investigators were brought in to spend a week or two uncovering the facts. None of us knew Andrew very well but the few times I met him he was respectful, gracious and excited about his future as an army officer and pilot.

Thoughts now turned to his family in Maryborough in country Qld and the funeral. I was asked if I would like to be on the firing party for the funeral. All military funerals have a firing party consisting of a dozen armed soldiers who pay their respects to the fallen. At the end of the service they fire, on command, a volley of 7 shots into the air. Given I had worked on the helicopter Andrew was flying just prior to the accident, I volunteered.

Dressed in full ceremonial dress we took a bus complete with a full esky of beer for the 4 x hour drive to Maryborough. The beer was for the return trip after what we thought would be a long day on our feet. The church for the service was outside Maryborough, in a beautiful bush setting miles from civilisation. We waited outside the tiny church which was chockers with family and friends, and stayed in formation for over an hour for the service to finish. After the coffin was brought out, the Last Post was played and we were given the command to shoot. The noise of the first round scattered the local birdlife and the screeching of hundreds of birds reverberated around the church.

By the time we got the seventh shot out, the assembled guests were a sobbing mess. All of us in the firing party felt the same way and as we hopped back on the bus, the mood was maudlin to say the least. Our thoughts immediately went to Andrew’s parents and how unimaginable it must have been to lose a child with so much future ahead of him. The beers were barely touched as we all stared out of our respective windows in complete silence on the way home.

The investigation findings

In aviation, safety is first and foremost as you can imagine. As a mechanic there are some procedures that are top of mind every single day. FOD (foreign object damage) means that everything is clean and accounted for whether that be the cleanliness in the hangar or the location of your tools, because you simply can’t afford to have anything disappear into an engine or transmission that shouldn’t be there. A big part of FOD mentality is your tool management. Every time you take a tool from the shadow board it must be replaced with 2 x metal discs, one has your name on it and the other is the aircraft number. If, at the end of the day you can’t find a tool, you should at least have some idea where it went and if you still cant find it, no one goes home until you do.

The second red flag that is ingrained into all aviation tradesmen is the “signing of the book”. Every piece of maintenance completed on an aircraft must be signed for. If an aircraft crashes, it will clearly show who did the work. Penalties involving misuse of the “book” especially if there is a fatality, can be up to 20 years in gaol.

Army aircraft servicing’s were classed R1, R2 and R3, with R3 being the most comprehensive and time consuming. In the week leading up to Andrew’s accident, I had been working on an R1 on that particular helicopter. Also during that week I was assigned to do “Duty Crew” which meant sitting in an observation room on the tarmac with the other assigned tradies, for a week doing “turnarounds”. All that means is you are looking after the aircraft flying in and out of the tarmac and “kicking the tyres” , making sure all your maintenance area (flight controls, skin etc) are ok, then the aircraft gets refuelled and back in the air. It can get hectic and I should never have been doing both the R1 and Duty Crew simultaneously.

During the R1, part of the job is to remove the hub (or rotor head) and propellor blades off the mast of the Bell 206B, drain the oil in the hub, replace the seals, replace the hub and blades to the mast, tighten the giant mast nut (which connects the hub to the mast) to the required PSI and lock-wire the nut. I had got to the point of replacing the seals when I was called away to Duty Crew. I asked my colleague, Cpl Pearce if he could finish it off and I would come back when I get a chance and check it. He obliged.

I returned to see the helicopter with all it’s pieces back together so I climbed up to check the mast nut and to look through the glass cover on the hub to see if the oil was full. All good, so I went ahead and signed “The Book”.

Six weeks after Andrew’s accident I got called to see WO1 (Warrant Officer Class 1 is the highest non-commissioned rank in the army) Len Avery, a highly respected man with a head like a Hereford Bull and fingers like continental sausages. He also had very distinguishable tattoos that looked like they were done in the back of a Saigon whore house during his 3 x tours of Vietnam. One wrist had the classic hula dancer with the grass skirt and the other, a black panther. Both were so dodgy they had amortised into his skin and were now nothing more than giant navy blue smudges. A legend of a man was WO1 Avery but I was nervous as to why he had called me into his office.

There were 2 x sample bottles of oil on his desk. He told me to sniff them and tell him what they were. “This is hydraulic oil Sir”, I squeaked out. “Hub oil right?” “Of course Sir.” (Gulp) “And this one?”, he said pointing to the other one. ” Jet 2 engine oil Sir”. “And which one do you reckon they found in the hub of the crashed chopper son?” I couldn’t speak and my heart sunk as I pictured myself manacled and dragged off to prison. He appeased me by saying that having the wrong oil in the hub didn’t contribute to the crash but asked “have you learned anything?” (Shit yeah) “Yes Sir”. He already knew that Pearce had put the wrong oil in the hub and that I had trustingly signed for it. Pearce and I were both charged but not punished. If I had pushed back and not worked on 2 x jobs concurrently, it would never have occurred.

When I finally caught up with Cpl Pearce I found him to be, shall we say, fairly ambivalent and laissez faire about his part in the misdemeanour but I “gently” managed to persuade him to donate significantly to a gift and flowers which we sent to Andrew’s parents. We never spoke again.

At 57 and with 2 x daughters in their 20’s, writing this exacerbates all those feelings I had in Maryborough that day and the overwhelming mournfulness that comes with a military funeral. I honestly can’t imagine how I would feel if I lost a child and the strength Andrew’s parents showed that day was extraordinary. I’m sure Andrew is never far away from them. Vale Andrew.

Bell 206B’s lined up on tarmac Oakey

Visiting RAAF Iroquois, Oakey

Porter line up Oakey

Bell 206B

Bell 206B taking off Oakey

Ceremonial dress, 1980’s

Firing party Korea 1953

Firing party Korea 1953